114 W. Broadway Street, Enid, Oklahoma

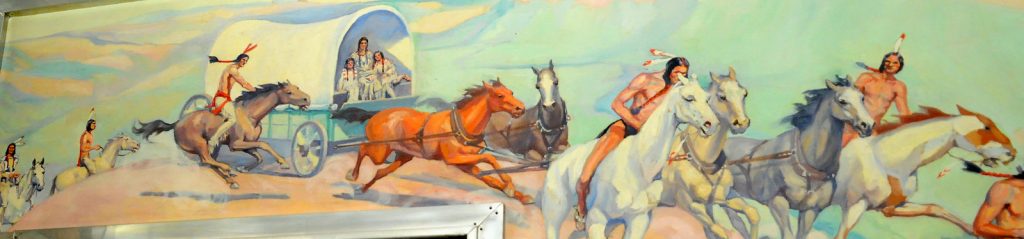

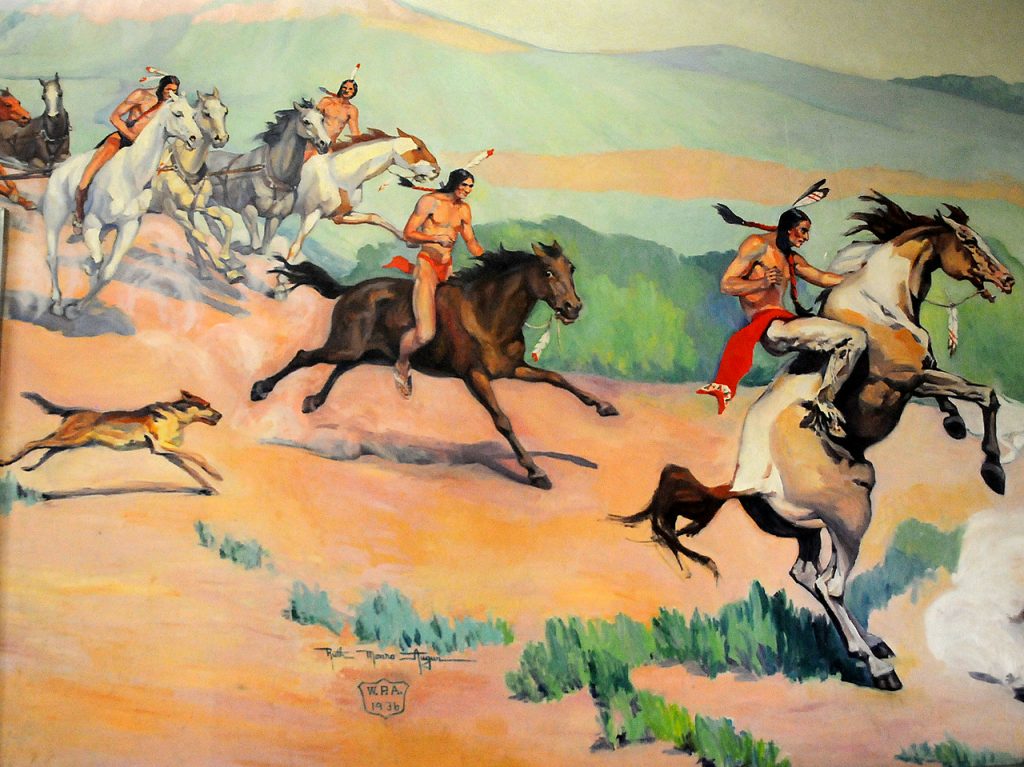

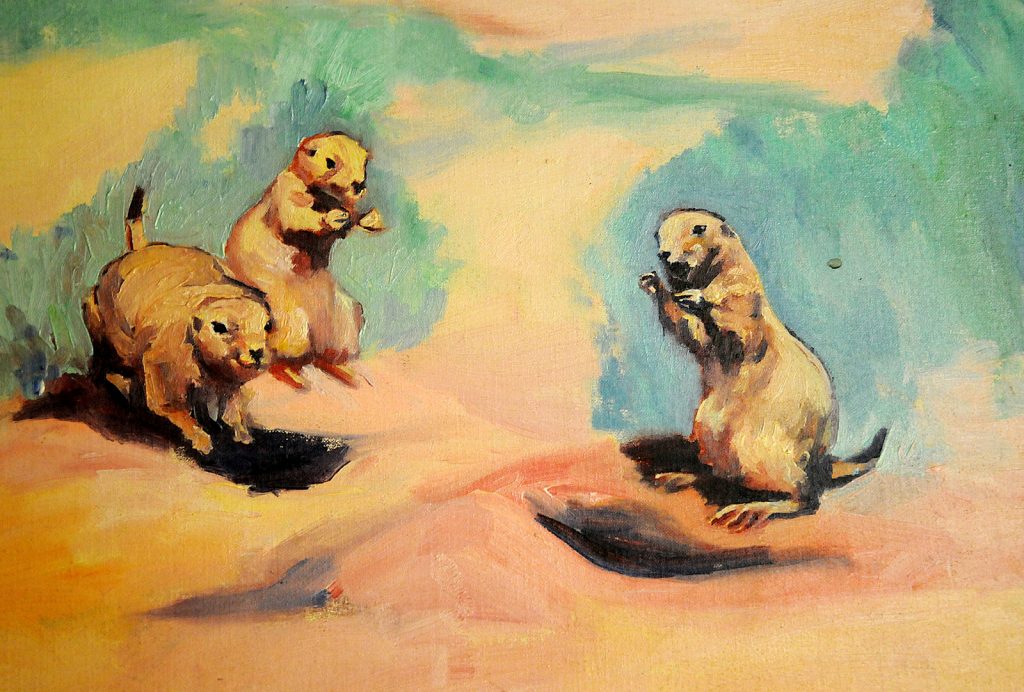

Decorating several of the interior halls and walls, Ruth Monro Augur painted a mural cycle depicting selected stages in the settlement of history of the region. The art was produced as a result of the WPA Federal Art Project and is unique because it represents the only extant and in situ example of a mural cycle completed int he state with WPA/FAP sponsorship. This mural cycle traces the long history of region that became Oklahoma from Native American life before European contact, to the arrival of the Europeans, and finally to the development of commerce and industry with the creation of the territory and state. During the 1930s, individual states became increasingly interested in both American history and their unique role in it. Eastern states began to rediscover and restore the disintegrating relics of their colonial past, and western states looked tot their frontier history with a fresh perspective. Native American life before European contact and the expedition of Spanish General Francisco Vasquez de Coronado became a favorite subject for western states hoping to attract tourists. Augur created her mural in that spirit, and she insisted on accuracy in the dress and accouterments. Her naturalistic style emphasizes this desire for accuracy, while the bright coloration hints at the bright light of the region. The choice of a largely pastel palette may also betray the influence of California Impressionism and Augur’s training in that state. The Enid cycle differs from many New Deal murals in that a carefully defined space had not been created for murals. Augur was forced to work around the architectural quirks of the courthouse, which contained long, narrow strips of space adjacent to the larger expanses of wall space. She often filled those problematic areas with anecdotal details, particularly with scenes of wildlife. In addition, she used maps and didactic text to fill in these spaces, creating an educational component uncommon to must New Deal murals.

Augur’s cycle provides an expansive view of both Enid and Oklahoma history from its prehistory to its territorial past. The murals offer a progressive view of modernization leading to the implied transition to the state of Oklahoma.

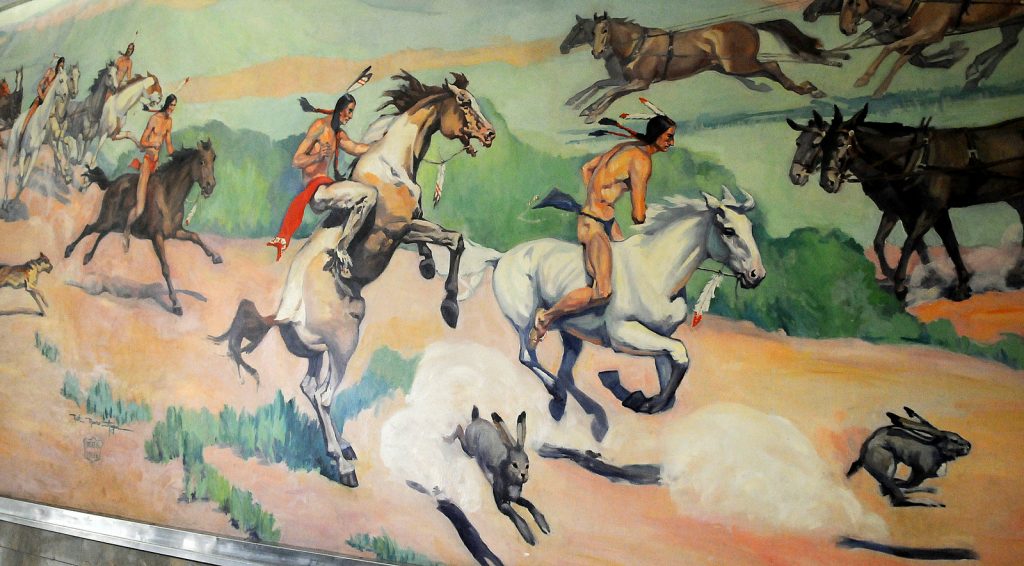

The Hunting Trail

Auglur begins the cycle with this mural which depicts bison hunting techniques before the arrival of Europeans and the importation of horses. At left, bison graze freely on the rolling plains of the region, and Augur adds a touch of humor to this otherwise tranquil scene by introducing a dialogue between a bull and two jackrabbits. However, chaos will soon erupt when the hunters, disguised under bison robes to affect a stealthy approach, unleash their arrows on the unsuspecting herd. The women wait atop the butte in the meantime to begin their job of skinning and butchering the fallen bison.

Map of the Southwestern United States

Tracing the Coronado’s journey which creates a transition to the next mural in the cycle.

The Explorer’s Trail

This depicts Coronado’s crossing of the Cherokee Strip in June 1541 during his North American search for Cibola or the fabled cities of gold. Led by the Pawnee slave named Turk, Coronado began a trek northward and arrived at Wichita territory in southern Kansas before realizing the futility of his mission. Augur created an elaborate parade of Spanish military in their armor and pomp. She conspicuously added a Franciscan friar, probably Fray Marcos de Niza who first told Coronado of Cibola. As Coronado progresses through the territory that will eventually become Oklahoma, his progress is carefully observed by Plains Indians, who send smoke signals to warn of the Europeans approach. The narrow strip at the extreme right provided a problematic space that Augur filled with a roadrunner to add a touch of local flavor. The Explorer’s Trail subtly prepares the viewer for the next mural The Cattle Trails through the Presence of Cornado’s team of horses. Cornado brought approximately 1,000 horses to North America, but lost many during his expedition. The strays bred and created the extensive wild herds in the West. Proliferation of these herds encouraged the growth of ranching in the West.

The Explorer’s Trail

The Explorer’s Trail

The Explorer’s Trail

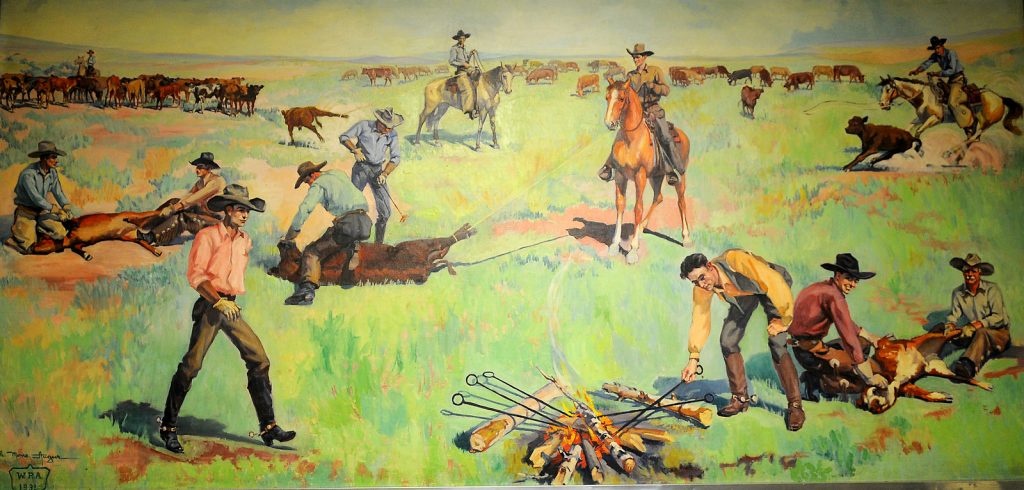

The Cattle Trails

Augur dated this mural historically in 1866-1886 because it depicts the days of the large cattle drives. Augur has flanked the mural with another map tracing the three major trails from Texas, The Western, The Chisholm, and The Shawnee, which passed through Indian Territory and into Kansas. Brands from various ranches frame the map and provide a decorative, albeit historical context for the adjacent scene of an 1860s cattle drive. In 1866 following the conclusion of the Civil War, Texan cattlemen began to drive beef cattle to western Kansas primarily via the Chisholm Trail to Abilene. The Chisholm passed through present-day Enid, and Angur has depicted and extensive Texan herd watering in the area known as Government Springs Park. Like the previous murals, the artist filled the scene with anecdotal details such as the chuck wagon circle and the arrival of a large herd to the watering hole. Augur attempted to maintain her commitment to veracity in the details of dress and objects, but some influence from the romatic Hollywood cowboys of the 1930s appears in the group standing at center.

The Cattle Trail

The Cattle Trail

The Cattle Trail

The Cattle Trail

The Cattle Trail

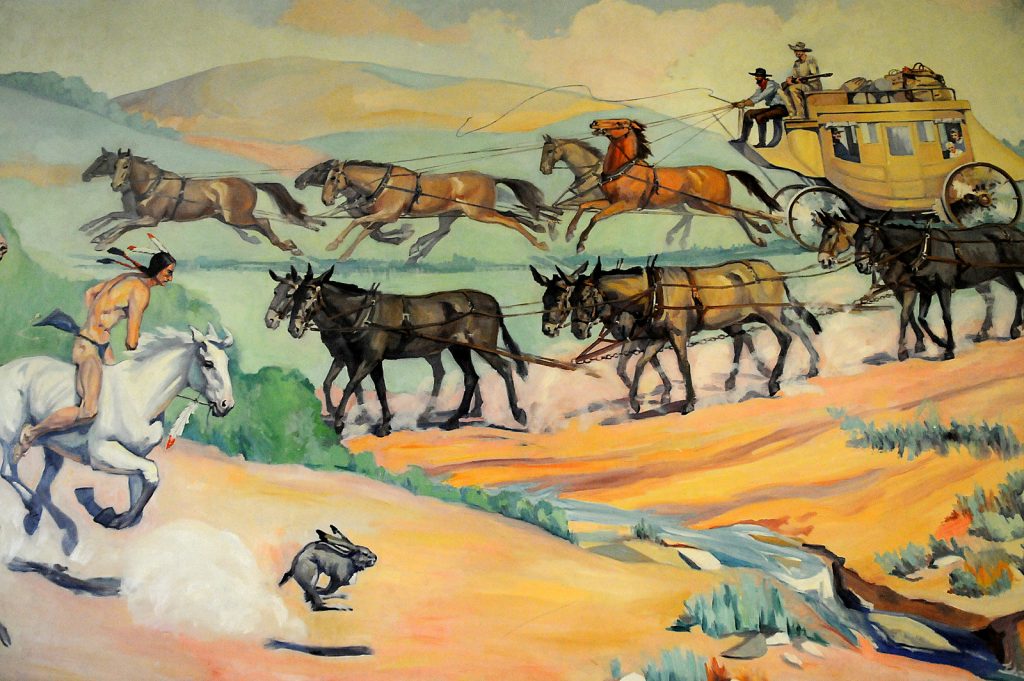

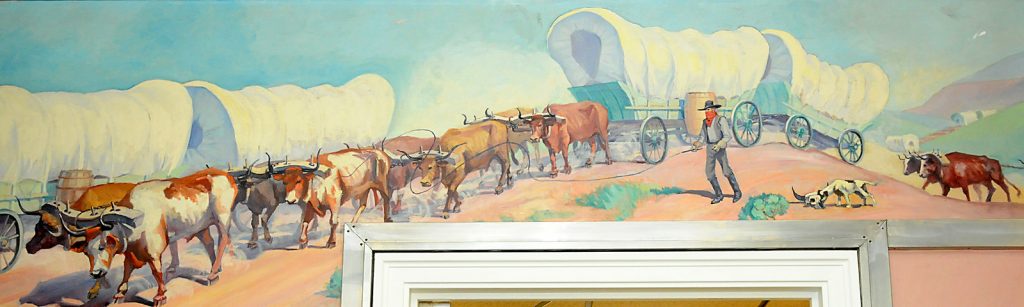

The Commerce Tail

Compares closely in the theme since it depicts the transportation of goods by animal before steam-powered locomotion. Augur dated The Commerce Trail between 1855-1893, and attempted to capture every form of transportation used in the commerce of this period. At right, oxen teams driven by bull-whackers hauled heavy loads within the territory and to surrounding states at a relatively slow pace, while smaller loads could be delivered faster by mule trains drive by mule-skinners. The horse-driven stagecoaches in the background offered the most expedient service. Deliveries to tribal reservations were generally handled by Indian freighters, which used surplus U.S. Army wagons and gear. Augur suggests that these freights, pictured at left, were relatively complicated with numerous warriors ensuring the safe transportation of the load to the reservation. Both the large drives of The Cattle Trails and the transportation methods of The Commerce Trail ceased almost entirely when the railroads entered Indian Territory in 1886 and official settlement of Oklahoma Territory began in 1889.

The Commerce Trail

The Commerce Trail

The Commerce Trail

The Commerce Trail

The Commerce Trail

The Commerce Trail

The Commerce Trail

The Commerce Trail

The Homemaker’s (Home-Seeker’s) Trail

The land runs that brought American settlers into Oklahoma Territory is depicted in Augur’s cycle The Homemaker’s Trail. Augur starts by the Cherokee Strip run on 16 September 1893, which opened the territory that would include Enid. Military officials have signaled the official beginning and hundreds of settlers create clouds of dust as they race ahead to stake their land claims. Augur relied on photographs of the actual run to inform her image.

The Rancher’s Trail

The final image in the cycle, The Rancher’s Trail, returns the theme of commerce but after the land runs, which promoted the growth of large ranches. Although the roping and herding of cattle is included in the image, Augur focuses most of her attention on the branding of calves indicating the careful control of property that came with official settlement of the territory.

The Rancher’s Trail

The Rancher’s Trail

The Rancher’s Trail

Ruth Monro Augur

Born in Austin, Texas and raised in Denver, Colorado where she studied at the Student School of Art, Ruth Auger became an artist of the West, with her most recognized achievement being six murals, completed in 1937 and covering 1136 square feet, of the history of the Cherokee Strip Run for the courthouse in Enid, Oklahoma. “The cattle portrayed in the mural bear registered Texas brands selected by the University of Texas, Austin”.

As a painted, she also depicted army officer and other portraits, horse studies, mountain landscapes, and cowboy figures.

In 1905 she won a scholarship to the New York School of Art, where she was a student of Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase. About ten years later, she studied in California at Carmel for summer school, the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco, and the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles.

She spent many years in the newspaper business, with art being a secondary activity. From 1917 to 1929, she was registrar at the Texas College of Mines and Metallurgy and was also a society editor for the “El Paso Herald” and the “El Paso Times”.

Then she won the WPA commission to paint the murals in Enid, and in 1937 settled permanently in that town. For 25 years, she served as staff artist for the Harlow Publishing Company, and many of her illustrations had western themes. She also taught at the Municipal Art Gallery. Much of her fine art painting was completed in her spare time from her professional jobs. On some of her paintings, she signed her last name “Auger.” [In 1934 she was commissioned by the Works Progress Administration WPA to paint historical murals in the Garfield County Courthouse in Enid, Oklahoma. She painted a total of five murals. With Native American scenes, she painted accurate dress and accouterments.

Ruth Monro Augur, 80, of 1219 Military Court, a longtime city portrait and commercial artist who painted panels depicting the history of the Episcopal church in St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral, died Friday at St. Anthony Hospital.

Services will be at 1 pm Monday in the chapel of St. Paul’s Cathedral, with burial at Rose Hill Cemetery under direction of Guardian Funeral Home.

Born in Austin, she grew up in. Denver, and studied at the New York School of Art, before moving to Oklahoma City about .5 years ago to head the art school of the Oklahoma Art Center.

Two years later, she the left that position to become staff artist for Harlow Publishing Co., where she was employed until she retired in 1965. She was well known for her murals in the Garfield County Court House and her portraits in the collection of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

She belonged to Oklahoma League for Conservative Art and was a lifetime member of the Episcopal church. She left no known survivors.[3]

Recent Comments