Description

This is a one-story brick building with basement that was designed in the Federal Revival style with a simple, symmetrical facade, modillions, and cornice returns on the gable ends. A keyed round arch with a sunburst motif frames the entrance. Matching eyebrow windows decorate the gable peaks and continue the sunburst design. This building is in very good condition. The mural, Roman Nose Canyon by Edith Mahier, decorates the north wall. Because of its architecture and art, this building is potentially eligible for listing in the National Register. The art is significant because of its connection with the New Deal, and the local history of Watonga-specifically a manufactured controversy to bring attention to the mural and the town.

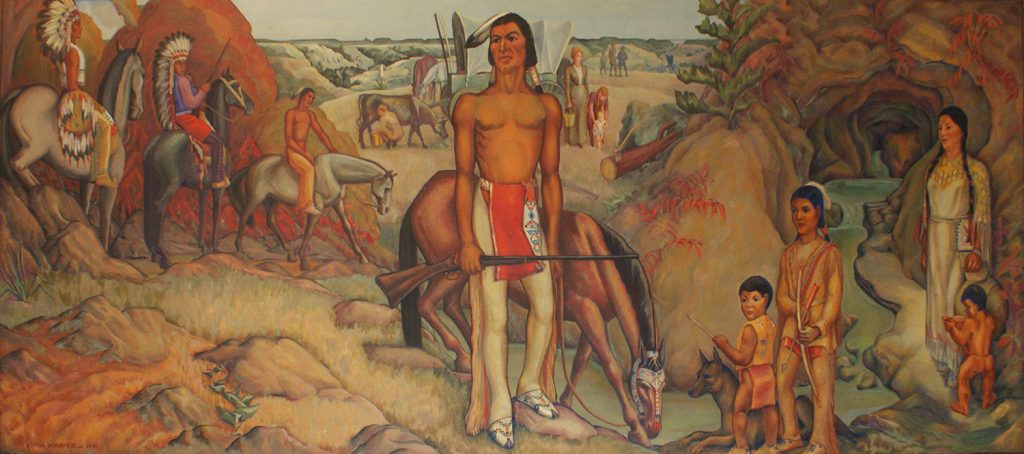

Roman Nose Canyon

by Edith Mahier, 1941, oil on canvas.

Edith Mahier’s Watonga Post Office mural, Roman Nose Canyon, is perhaps the best known of all New Deal murals in Oklahoma. Mahier skillfully incorporated local history and contemporary tourism in Roman Nose Canyon. It depicts both the Cheyenne’s confrontation with American settlers following the land run, and the surrounding landscape of Roman Nose Canyon, which had been the winter camp for the Cheyenne and was quickly becoming a contemporary destination for campers and naturalists. In the mural, Chief Henry Roman Nose stands at center with his wife, children, and fellow tribal members nearby. Roman Nose, or properly translated “Arched Nose,” was one of the most prominent Cheyenne leaders during the Indian Wars of the 1860s. He was noted particularly for his headdress made with one buffalo horn and a train of black and red eagle feathers, which Mahi er chose to omit in favor of a single feather.

The Cheyenne, who have come to water their horses, encounter settlers who have also come to water their livestock. For Mahier, the confrontation spelled the end of traditional Cheyenne life.

The settlers, also in search of water, have stopped their covered wagons near the stream, while they scan the horizon envisaging the gypsum pits, the flourishing wheat fields, and their future city with its churches, school, homes and business houses. The young Indian stands holding his rifle, his defiance gone, but in its place wonder, for he is old enough to realize that he may never achieve those honors which his father and grandfather held dear; that he must find his place under a new system.[3]

As such, Roman Nose Canyon examined the familiar theme of the “vanishing race,” which had received treatment in other New Deal murals. Its notoriety came from the sensation that the Watonga Chamber of Commerce staged following the mural’s installation. Gerald Curtin, owner and publisher of the Watonga Republican, organized a nine-day protest in June 1941 involving Chief Red Bird, grandson of Black Kettle, his wife Prairie Woman, and their children. Red Bird expressed his distaste for the mural in state papers through an interpreter Joe Yellow Eyes. The Cheyenne protesters condemned Roman Nose’s physique as that of a “Navajo jellybean,” his absence of a proper headdress, and his breech-cloth as too short. Mahler responded that “I entered the competition mainly because few Oklahoma artists were participating and they were sending out this way eastern artists who were putting English saddles on Indian ponies. At least I didn’t do that.” Her anxieties may have been calmed by Curtin’s assistant at the Watonga Republican, Ernie Hoberecht, who confided: “It’s a publicity stunt … and everyone knows it is a joke. In fact, it’ll probably make you more famous than you already are. “[4]

Mahier offered to repaint some sections of the mural but never did. Despite her presumed errors in the mural, she was fairly familiar with Native American culture. She spent much of her career at OU, and instructed a number of Native American artists such as Acee Blue Eagle and Dick West.

Sources

- Thematic Survey of New Deal Era Public Art in Oklahoma 2003-2004, Project Number: 03-401 (Department of Geography, Oklahoma State University)

- https://postalmuseum.si.edu/indiansatthepostoffice/mural41.html

- Edith Mahler, “A Few Thoughts on Mural Painting,” Records of the Public Buildings Service, Record Group Number 121, National Archives, Washington D. C.

- Edith Mahler and Hoberecht quoted in Kara! Ann Marling, Wall to Wall America: A Cultural History of PostOffice Murals in the Great Depression (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982 ), 2 79.

Supported Documents

- Chronicles of Oklahoma, Volume 66, Number 4, Winter 1988 Page: 374 – Watonga Day in the Sun or Trickster Comes to Town

Recent Comments